as a command economy, the soviet union was able to make what major change to russian agriculture?

Agriculture in the Soviet Wedlock was mostly collectivized, with some limited cultivation of private plots. It is frequently viewed equally 1 of the more inefficient sectors of the economy of the Soviet Wedlock. A number of food taxes (prodrazverstka, prodnalog, and others) were introduced in the early Soviet period despite the Prescript on Land that immediately followed the October Revolution. The forced collectivization and grade war against (vaguely divers) "kulaks" under Stalinism greatly disrupted farm output in the 1920s and 1930s, contributing to the Soviet dearth of 1932–33 (most especially the holodomor in Ukraine). A system of state and collective farms, known as sovkhozes and kolkhozes, respectively, placed the rural population in a system intended to be unprecedentedly productive and off-white merely which turned out to be chronically inefficient and lacking in fairness. Nether the administrations of Nikita Khrushchev, Leonid Brezhnev, and Mikhail Gorbachev, many reforms (such every bit Khrushchev's Virgin Lands Campaign) were enacted as attempts to defray the inefficiencies of the Stalinist agronomical arrangement. Yet, Marxist–Leninist ideology did not permit for any substantial amount of marketplace mechanism to coexist aslope central planning, so the private plot fraction of Soviet agronomics, which was its about productive, remained confined to a limited role. Throughout its afterward decades the Soviet Spousal relationship never stopped using substantial portions of the precious metals mined each year in Siberia to pay for grain imports, which has been taken by various authors every bit an economic indicator showing that the state'due south agriculture was never as successful as information technology ought to have been. The real numbers, however, were treated every bit state secrets at the fourth dimension, so accurate analysis of the sector's performance was limited exterior the USSR and nearly impossible to gather within its borders. However, Soviet citizens every bit consumers were familiar with the fact that foods, especially meats, were oft noticeably scarce, to the point that not lack of money so much as lack of things to buy with information technology was the limiting factor in their standard of living.

Despite immense land resources, all-encompassing farm machinery and agrochemical industries, and a large rural workforce, Soviet agriculture was relatively unproductive. Output was hampered in many areas by the climate and poor worker productivity. Yet, Soviet subcontract functioning was not uniformly bad. Organized on a big scale and relatively highly mechanized, its state and collective agronomics made the Soviet Spousal relationship one of the globe's leading producers of cereals, although bad harvests (as in 1972 and 1975) necessitated imports and slowed the economy. The 1976–1980 five-yr plan shifted resources to agronomics, and 1978 saw a record harvest. Conditions were all-time in the temperate chernozem (black globe) belt stretching from Ukraine through southern Russian federation into the east, spanning the extreme southern portions of Siberia. In addition to cereals, cotton, sugar beets, potatoes, and flax were also major crops. Such functioning showed that underlying potential was not lacking, which was not surprising as the agriculture in the Russian Empire was traditionally amongst the highest producing in the globe, although rural social conditions since the October Revolution were hardly improved. Grains were more often than not produced by the sovkhozes and kolkhozes, but vegetables and herbs ofttimes came from private plots.

History [edit]

The term "Stalin'south revolution" has been used for this transition, and that conveys well its violent, destructive, and utopian grapheme.

Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism, Introduction, Milestones.

During the Russian Civil War, Joseph Stalin's experience every bit political chief of various regions, carrying out the dictates of state of war communism, involved extracting grain from peasants, including extraction at gunpoint from those who were not supportive of the Bolshevik (Scarlet) side of the war (such as Whites and Greens). Later on a grain crunch during 1928, Stalin established the USSR's organization of state and collective farms when he moved to replace the New Economic Policy (NEP) with commonage farming, which grouped peasants into commonage farms (kolkhozy) and land farms (sovkhozy). These commonage farms allowed for faster mechanization, and indeed, this period saw widespread utilize of farming mechanism for the first time in many parts of the USSR, and a rapid recovery of agricultural outputs, which had been damaged past the Russian civil war. Both grain production, and the number of farm animals rose above pre-civil war levels by early 1931, before major famine undermined these initially skillful results.[1]

At the same time, individual farming and khutirs were liquidated through class discrimination identifying such elements as kulaks.[one] In the Soviet propaganda kulaks were portrayed every bit counterrevolutionaries and organizers of anti-Soviet protests and terrorist acts. In Ukraine the Turkic name "korkulu" was adopted, which meant "dangerous".[ii] The word itself is foreign to Ukraine. According to the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia, struggle with kulaks in Ukraine was taking place more intensely than anywhere else in the Soviet Wedlock.[2] [3]

Coincidentally with the start of First "pyatiletka" (five twelvemonth plan), a new commissariat of the Soviet Matrimony was created, better known as Narkomzem (People'south Commissariat of Land Cultivation) led by Yakov Yakovlev. After the voice communication on collectivization that Stalin gave to the Communist Academy, there were no specific instructions on how exactly it had to exist implemented, except for liquidation of kulaks as a class.[4] Stalin's revolution is oft regarded as one of the factors which led to the severe Soviet famine of 1932–33, better known in Ukraine every bit the Holodomor. Official Soviet sources blamed the dearth on counterrevolutionary efforts by the Kulaks, though there is little testify for this claim.[5] [6] [7] A plausible alternative explanation, supported past some historians, is that the famine occurred at least in part due to poor weather condition conditions and depression harvests.[8] [9] [10] The famine started in Ukraine in the winter of 1931 and despite the lack of any official reports the news spread by word of mouth rapidly.[four] During that time restrictions on track travel were gear up past regime.[4] Only next yr in 1932-33 the famine spread outside of Ukraine to agricultural regions of Russia and Kazakhstan, while the "news blackout continued".[4] The famine led to the introduction of the internal passport system, due to the unmanageable catamenia of migrants to the cities.[4] The famine finally concluded in 1933, later on a successful harvest.[viii] Collectivization continued. During the second five-twelvemonth plan Stalin came upward with another famous slogan in 1935: "Life has get better, life has become more cheerful." Rationing was lifted.[4] In 1936, due to a poor harvest, fears of another dearth led to famously long breadlines.[four] However, no such famine occurred, and these fears proved largely unfounded.

During the 2nd five-yr plan, under the policy of "cultural revolution" , the Soviet government established fines that were collected from farmers. Citing Siegelbaum'south Stakhanovism in her book Everyday Stalinism, Fitzpatrick wrote: "...in a district in the Voronezh Region, 1 rural soviet chairman imposed fines on kolkhoz members totaling 60,000 rubles in 1935 and 1936: "He imposed the fines on any pretext and at his own discretion - for not showing up for work, for not attending literacy classes, for 'boorish language', for not having dogs tied up... Kolkhoznik Thousand. A. Gorshkov was fined 25 rubles for the fact that 'in his hut the floors were not done'".[iv]

Khrushchev Era 1955-1963 [edit]

Nikita Khrushchev was a top proficient on agricultural policies and looked especially at collectivism, state farms, liquidation of machine-tractor stations, planning decentralization, economic incentives, increased labor and capital investment, new crops, and new production programs. Henry Ford had been at the center of American engineering transfer to the Soviet Marriage in the 1930s; he sent over factory designs, engineers, and skilled craftsmen, as well as tens of thousands of Ford tractors. By the 1940s Khrushchev was keenly interested in American agricultural innovations, especially on large-scale family-operated farms in the Midwest. In the 1950s he sent several delegations to visit farms and state grant colleges, looking at successful farms that utilized loftier-yielding seed varieties, very large and powerful tractors and other machines, all guided past modern direction techniques.[11] Especially afterward his visit to the United states of america in 1959, he was keenly aware of the demand to emulate and even friction match American superiority and agricultural technology. [12] [13]

Khrushchev became a hyper-enthusiastic crusader to abound corn (maize).[14] He established a corn institute in Ukraine and ordered thousands of hectares to be planted with corn in the Virgin Lands. In 1955, Khrushchev advocated an Iowa-style corn belt in the Soviet Union, and a Soviet delegation visited the U.South. state that summer. The delegation chief was approached past farmer and corn seed salesman Roswell Garst, who persuaded him to visit Garst'due south big farm.[15] The Iowan visited the Soviet Union, where he became friends with Khrushchev, and Garst sold the USSR 5,000 curt tons (4,500 t) of seed corn. Garst warned the Soviets to grow the corn in the southern function of the country and to ensure there were sufficient stocks of fertilizer, insecticides, and herbicides.[16] This, notwithstanding, was non done, as Khrushchev sought to plant corn fifty-fifty in Siberia, and without the necessary chemicals. The corn experiment was not a great success, and he later complained that overenthusiastic officials, wanting to please him, had overplanted without laying the proper background, and "equally a outcome corn was discredited as a silage crop—and so was I".[17]

Khrushchev sought to abolish the Machine-Tractor Stations (MTS) which not only owned most big agricultural machines such as combines and tractors merely besides provided services such as plowing, and transfer their equipment and functions to the kolkhozes and sovkhozes (country farms).[18] After a successful exam involving MTS which served one large kolkhoz each, Khrushchev ordered a gradual transition—but and then ordered that the change take place with groovy speed. Within 3 months, over half of the MTS facilities had been closed, and kolkhozes were being required to buy the equipment, with no discount given for older or battered machines. MTS employees, unwilling to demark themselves to kolkhozes and lose their state employee benefits and the right to change their jobs, fled to the cities, creating a shortage of skilled operators. The costs of the machinery, plus the costs of building storage sheds and fuel tanks for the equipment, impoverished many kolkhozes. Inadequate provisions were made for repair stations. Without the MTS, the marketplace for Soviet agricultural equipment fell autonomously, equally the kolkhozes now had neither the money nor skilled buyers to purchase new equipment.[19]

In the 1940s Stalin put Trofim Lysenko in charge of agronomical research, with his beatnik ideas that flouted modern genetics science. Lysenko maintained his influence under Khrushchev, and helped block the adoption of American techniques.[20] In 1959, Khrushchev announced a goal of overtaking the United States in the production of milk, meat, and butter. Local officials kept Khrushchev happy with unrealistic pledges of production. These goals were met past farmers who slaughtered their breeding herds and by purchasing meat at state stores, then reselling it back to the government, artificially increasing recorded product.[21] In June 1962, food prices were raised, peculiarly on meat and butter, by 25–30%. This acquired public discontent. In the southern Russian urban center of Novocherkassk (Rostov Region), this discontent escalated to a strike and a defection against the authorities. The revolt was put down by the military machine. According to Soviet official accounts, 22 people were killed and 87 wounded. In addition, 116 demonstrators were convicted of interest and seven of them executed. Information about the defection was completely suppressed in the USSR, but spread through Samizdat and damaged Khrushchev'south reputation in the West.[22]

Drought struck the Soviet Union in 1963; the harvest of 107,500,000 short tons (97,500,000 t) of grain was down from a tiptop of 134,700,000 short tons (122,200,000 t) in 1958. The shortages resulted in bread lines, a fact at first kept from Khrushchev. Reluctant to purchase food in the West,[23] but faced with the alternative of widespread hunger, Khrushchev exhausted the nation's hard currency reserves and expended role of its gold stockpile in the purchase of grain and other foodstuffs.[24] [25]

Agronomical labour [edit]

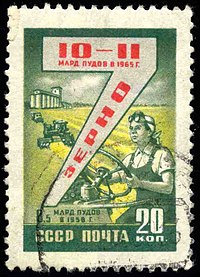

Soviet Union postage stamp, the seven-twelvemonth plan, grain; 1959, 20 kop., used, CPA No. 2345.

It had been the leaders' hope that the peasantry could exist made to pay about of the costs of industrialization; the collectivization of peasant agriculture that accompanied the first five-year plan was intended to achieve this consequence by forcing peasants to accept low state prices for their appurtenances.

Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism, Introduction, Milestones.

Stalin'due south entrada of forced collectivization relied on a hukou arrangement to proceed farmers tied to the land. The collectivization was a major gene explaining the sector's poor performance. It has been referred to as a grade of "neo-serfdom", in which the Communist hierarchy replaced the quondam landowners.[26] In the new state and commonage farms, outside directives failed to take local growing weather into account, and peasants were often required to supply much of their produce for nominal payment.

Also, interference in the day-to-day diplomacy of peasant life often bred resentment and worker alienation across the countryside. The human toll was very large, with millions, maybe as many equally 5.three million, dying from famine due largely to collectivisation, and much livestock was slaughtered by the peasants for their own consumption.[27] In the commonage and state farms, low labor productivity was a issue for the entire Soviet period.[28] As in other economic sectors, the authorities promoted Stakhanovism every bit a ways to amend labor productivity. This system was thrilling to a few workers who had both the talent and the vanity to make everyone else's performance expect bad, but it was generally regarded equally dispiriting and a form of apple polishing by most workers, especially in the subsequently decades of the union, when socialist idealism had become moribund among the rank-and-file. It too tended to be destructive of the state'due south majuscule equipment, which was thrashed and soon trashed instead of being well maintained.

The sovkhozy tended to emphasize larger scale production than the kolkhozy and had the ability to specialize in certain crops. The government tended to supply them with amend machinery and fertilizers, not least considering Soviet ideology held them to be a higher step on the scale of socialist transition. Motorcar and tractor stations were established with the "lower form" of socialist farm, the kolkhoz, mainly in mind, considering they were at first not trusted with ownership of their own capital equipment (as well "backer") equally well as non trusted to know how to utilise it well without close pedagogy. Labor productivity (and in plough incomes) tended to be greater on the sovkhozy. Workers in state farms received wages and social benefits, whereas those on the commonage farms tended to receive a portion of the net income[ citation needed ] of their farm, based, in part, on the success of the harvest and their individual contribution.

Although accounting for a small-scale share of cultivated area,[ citation needed ] private plots produced a substantial share of the state's meat, milk, eggs, and vegetables.[29]

The individual plots were also an of import source of income for rural households. In 1977, families of kolkhoz members obtained 72% of their meat, 76% of their eggs and most of their potatoes from individual holdings. Surplus products, as well every bit surplus livestock, were sold to kolkhozy and sovkhozy and also to land consumer cooperatives. Statistics may actually under-stand for the total contribution of private plots to Soviet agriculture.[30] The just fourth dimension when private plots were completely banned was during collectivization, when famine took millions of lives.[31]

Efficiency or inefficiency of commonage farming [edit]

The theme that the Soviet Union was not getting adept enough results out of its farming sector, and that the top leadership needed to accept pregnant actions to correct this, was a theme that permeated Soviet economics for the entire lifespan of the wedlock. In the 1920s through 1940s, the commencement variation on the subject was that counter-revolutionary subversive wrecking demand to be ferreted out and violently repressed. In the late 1950s through 1970s, the focus shifted to lack of technocratic finesse, with the idea that smarter technocratic direction would fix things. By the 1980s, the terminal variation of the theme was a bifurcation betwixt people who wanted to essentially shake upward the nomenklatura system and those who wanted to double down on its ossification.

After Stalin died and a troika belatedly emerged, Georgy Malenkov proposed agricultural reforms. But in 1957, Nikita Khrushchev achieved a purge of that troika and began proposing his reforms, of which the Virgin Lands Entrada is the well-nigh famous. During and after Khrushchev'south premiership, Alexei Kosygin wanted to reorganize Soviet agriculture instead of increasing investments. He claimed that the main reason for inefficiency in the sector could be blamed on the sector'southward infrastructure. Once he became the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, he was able to direct the 1965 Soviet economic reform.

The theory behind collectivization included not only that it would be socialist instead of backer but likewise that information technology would replace the small-scale unmechanized and inefficient farms that were then commonplace in the Soviet Union with large-scale mechanized farms that would produce food far more efficiently. Lenin saw private farming as a source of backer mentalities and hoped to replace farms with either sovkhozy which would make the farmers "proletarian" workers or kolkhozy which would at least be collective. Withal, most observers say that despite isolated successes,[32] collective farms and sovkhozes were inefficient, the agronomical sector existence weak throughout the history of the Soviet Union. [33]

Hedrick Smith wrote in The Russians (1976) that, according to Soviet statistics, one fourth of the value of agricultural production in 1973 was produced on the private plots peasants were allowed (2% of the whole arable country).[34] In the 1980s, iii% of the land was in individual plots which produced more than a quarter of the total agricultural production.[35] i.east. private plots produced somewhere effectually 1600% and 1100% equally much every bit common ownership plots in 1973 and 1980. Soviet figures claimed that the Soviets produced 20–25% equally much every bit the U.S. per farmer in the 1980s.[36]

This was despite the fact that the Soviet Union had invested enormously to agronomics.[36] Production costs were very high, the Soviet Matrimony had to import food, and it had widespread food shortages even though the country had a large share of the all-time agricultural soil in the world and a high land/population ratio.[36]

The claims of inefficiency have, however, been criticized by ofttimes described as Neo-Marxist Economist Joseph E. Medley of the Academy of Southern Maine, US.[37] Statistics based on value rather than volume of production may give one view of reality, as public-sector food was heavily subsidized and sold at much lower prices than private-sector produce. As well, the two–three% of arable land allotted as private plots does not include the large surface area allocated to the peasants equally pasturage for their private livestock; combined with country used to produce grain for fodder, the pasture and the individual plots full near xx% of all Soviet farmland.[37] Private farming may also exist relatively inefficient, taking roughly twoscore% of all agricultural labor to produce just 26% of all output by value. Another problem is these criticisms tend to discuss merely a small number of consumer products and do non take into account the fact that the kolkhozy and sovkhozy produced mainly grain, cotton wool, flax, forage, seed, and other non-consumer appurtenances with a relatively low value per unit area. This economist admits to some inefficiency in Soviet agriculture, simply claims that the failure reported by most Western experts was a myth.[37] He believes the above criticisms to be ideological and emphasizes "[t]he possibility that socialized agronomics may be able to make valuable contributions to improving homo welfare".

In pop culture [edit]

Soviet civilization presented an agro-Romantic view of country life. After the fall of Soviet Wedlock, information technology has been recreated natural language-in-cheek in the albums and videos of the Moldovan group Zdob şi Zdub.

Research [edit]

The Tsar'southward Petrovskaya Agricultural Academy was taken over during the Revolution and renamed the Moscow Agricultural Constitute. (Today known as the Russian State Agrarian University – Moscow Timiryazev Agronomical Academy.) One of its graduates was Nikolai Vavilov, who would go on to contribute greatly - albeit controversially during Stalin's rule. Vavilov was greatly disliked by Lysenko but afterward his decease was recognised as a hero to Soviet agricultural inquiry and indeed to agricultural science worldwide.[38]

Under Supreme Soviet legislation the experimental plots/fields of agricultural enquiry and agronomical educational institutions were inviolable, non to be seized and repurposed even by state agencies. Exceptions could be fabricated rarely and just by the USSR or Republic governments themselves.[39]

Run into also [edit]

- Agriculture in Russia

- Agriculture in the Russian Empire

- Bibliography of the Russian Revolution and Ceremonious War § Peasants

- Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Agronomics and the peasantry

- Bibliography of the Post Stalinist Soviet Union § Rural life and agriculture

- Famines in Russia and USSR

- Passport system in the Soviet Spousal relationship

- Trofim Lysenko

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b Власов М. (1932). "Сельское хозяйство СССР за пятнадцать лет диктатуры пролетариата". Народное хозяйство СССР. Экономико-статистический журнал. pp. 72–91. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ a b Korkulism at the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia.

- ^ Robert Conquest (1987). The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-famine. Oxford University Printing. pp. 159–. ISBN978-0-19-505180-three . Retrieved sixteen August 2013.

- ^ a b c d eastward f thousand h Fitzpatrick, Sh. Everyday Stalinism. "Oxford Printing". 1999. p 6.

- ^ "Ukraine's Holodomor". The Times. Uk. 1 July 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ^ According to Alan Bullock, "the total Soviet grain ingather was no worse than that of 1931 ... information technology was non a crop failure but the excessive demands of the country, ruthlessly enforced, that price the lives of as many every bit five 1000000 Ukrainian peasants." Stalin refused to release big grain reserves that could have alleviated the famine, while continuing to export grain; he was convinced that the Ukrainian peasants had hidden grain away and strictly enforced draconian new collective-farm theft laws in response. Bullock, Alan (1962). Hitler: A Report in Tyranny. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013564-ii.

- ^ Mark Harrison (2004). "The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia. Vol. 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933 by R.W. Davies and S.G. Wheatcroft" (PDF) (Review). Retrieved 28 Dec 2008.

- ^ a b "Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933" (PDF). The Carl Brook Papers in Russian and Eastward European Studies. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 Baronial 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "[T]he drought of 1931 was particularly severe, and drought conditions connected in 1932. This certainly helped to worsen the conditions for obtaining the harvest in 1932." Davies, R. W.; Wheatcroft, S. Thousand. (2002). "The Soviet Famine of 1932-33 and the Crisis in Agriculture". In Wheatcroft, Due south. G. (ed.). Challenging Traditional Views of Russian History (PDF). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 69–91.

- ^ Tauger, Mark B. (2001). "Natural Disasters and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933." The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & Eastward European Studies (University of Pittsburgh) (1506). Page 46. "This famine therefore resembled the Irish famine of 1845–1848, but resulted from a litany of natural disasters that combined to the aforementioned effect as the spud blight had ninety years before, and in a similar context of substantial nutrient exports."

- ^ Aaron Unhurt-Dorrell, "The Soviet Spousal relationship, the U.s.a., and Industrial Agronomics" Journal of World History (2015) 26#ii pp 295–324.

- ^ Lazar Volin, "Soviet agriculture nether Khrushchev." American Economical Review 49.ii (1959): xv-32 online.

- ^ Lazar Volin, Khrushchev and the Soviet agricultural scene (U of California Printing, 2020).

- ^ Aaron Hale-Dorrell, Corn Crusade: Khrushchev'southward Farming Revolution in the Post-Stalin Soviet Spousal relationship (2019) PhD dissertation version.

- ^ Stephen J. Frese, "Comrade Khrushchev and Farmer Garst: East-Due west Encounters Foster Agronomical Exchange." The History Teacher 38#1 (2004), pp. 37–65. online.

- ^ William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2003), p 373.

- ^ Taubman 2003, p. 373.

- ^ Roy Medvedev and Zhores Medvedev, Khrushchev: The Years in Power (1978), p. 85.

- ^ Medvedev & Medvedev 1978, pp. 86–93.

- ^ David Joravsky, The Lysenko Affair (1970) pp 172–180.

- ^ William J. Tompson, Khrushchev: A Political Life (1995) pp 214–16.

- ^ Taubman 2003, pp. 519–523.

- ^ Taubman 2003, p. 607.

- ^ Medvedev & Medvedev 1978, pp. 160–61.

- ^ Il'ia Due east. Zelenin, "N. South. Khrushchev's Agrestal Policy and Agriculture in the USSR." Russian Studies in History fifty.3 (2011): 44-70.

- ^ Fainsod, Merle (1970). How Russia is Ruled (revised ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Academy Press. pp. 570.

- ^ Hubbard, Leonard E. (1939). The Economic science of Soviet Agronomics. Macmillan and Co. pp. 117–eighteen.

- ^ Rutland, Peter (1985). The Myth of the Plan: Lessons of the Soviet Planning Experience . Essex: Open Court Publishing Co. pp. 110.

- ^ de Pauw, John W. (1969). "The Private Sector in Soviet Agronomics". Slavic Review. 28 (1): 63–71. doi:10.2307/2493038. ISSN 0037-6779.

- ^ Nove, Alec (1966). The Soviet Economic system: An Introduction. New York: Praeger. pp. 116–8.

- ^ Gregory, Paul R.; Stuart, Robert C. (1990). Soviet Economical Structure and Performance. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 294–5 and 114.

- ^ Zaslavskaya, Tatyana (Baronial 1990). The 2d Socialist Revolution (survey by a Soviet sociologist written in the tardily 1980s which advocated restructuring of the economy). Indiana Academy Press. p. 121. ISBN0-253-20614-half-dozen.

- ^ Zaslavskaya (1990), p. 22-23, 39, 54-56, 58-59, 68, 71-72, 87, 115, 166-168, 192.

- ^ Smith, Hedrick (1976). The Russians . Crown. p. 201. ISBN0-8129-0521-0.

- ^ "Soviet Wedlock - Policy and administration". Nations Encyclopedia (taustanaan United states of america:n kongressin kirjaston tutkimusaineisto). May 1989.

- ^ a b c Ellman, Michael (11 June 1988). "Soviet Agricultural Policy". Economic & Political Weekly. 23 (24): 1208–1210. JSTOR 4378606.

- ^ a b c "Soviet Agriculture: A Critique of the Myths Constructed past Western Critics". Archived from the original on xiv March 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-22 .

- ^ Pringle, Peter (2014). The murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The story of Stalin'south persecution of one of the great scientists of the twentieth century. New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 22–23. ISBN978-1-4165-6602-1. OCLC 892938236.

- ^ Gorbachev, Mikhail (1992). "Primal Principles of the Legislation of the USSR and the Union Republics on Land". Statutes and Decisions. Taylor & Francis. 29 (2): 48–69. doi:10.1080/10610014.1992.11501971. ISSN 1061-0014.

Cited sources [edit]

- Medvedev, Roy; Medvedev, Zhores (1978), Khrushchev: The Years in Ability, Due west.W. Norton & Co., ISBN978-0231039390

- Taubman, William (2003), Khrushchev: The Human being and His Era, W.W. Norton & Co., ISBN978-0-393-32484-6

Further reading [edit]

- Davies, Robert, and Stephen Wheatcroft. The years of hunger: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1933 (Springer, 2016).

- Davies, Robert William, and Richard W. Davies. The socialist offensive: the collectivisation of Soviet agriculture, 1929-1930 (London: Macmillan, 1980).

- Figes, Orlando. The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia. "Macmillan". 2008

- Frese, Stephen J. "Comrade Khrushchev and Farmer Garst: East-West Encounters Foster Agricultural Exchange." The History Teacher 38#1 (2004), pp. 37–65. online.

- Hale-Dorrell, Aaron. "The Soviet Marriage, the United States, and Industrial Agriculture" Journal of Globe History (2015) 26#ii pp 295–324.

- Unhurt-Dorrell, Aaron. Corn Cause: Khrushchev's Farming Revolution in the Post-Stalin Soviet Union (2019) PhD dissertation version.

- Hedlund, Stefan. Crisis in Soviet agriculture (1983).

- Hunter, Holland. "Soviet Agriculture with and without Collectivization, 1928-1940." Slavic Review 47.2 (1988): 203-216. online

- Karcz, Jerzy, ed. Soviet and East European Agriculture (1967)

- McCauley, Martin. Khrushchev and the Development of Soviet Agronomics: Virgin Land Program, 1953-64 (Springer, 2016).

- Volin, Lazar. "Soviet agriculture under Khrushchev." American Economic Review 49.ii (1959): 15-32 online.

- Volin, Lazar/ Khrushchev and the Soviet agricultural scene (U of California Printing, 2020).

montfordhismandent1980.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_the_Soviet_Union

0 Response to "as a command economy, the soviet union was able to make what major change to russian agriculture?"

Post a Comment